Tutorial

Understanding Database Sharding

Manager, Developer Education

Introduction

Any application or website that sees significant growth will eventually need to scale in order to accommodate increases in traffic. For data-driven applications and websites, it’s critical that scaling is done in a way that ensures the security and integrity of their data. It can be difficult to predict how popular a website or application will become or how long it will maintain that popularity, which is why some organizations choose a database architecture that allows them to scale their databases dynamically.

In this conceptual article, we will discuss one such database architecture: sharded databases. Sharding has been receiving lots of attention in recent years, but many don’t have a clear understanding of what it is or the scenarios in which it might make sense to shard a database. We will go over what sharding is, some of its main benefits and drawbacks, and also a few common sharding methods.

What is Sharding?

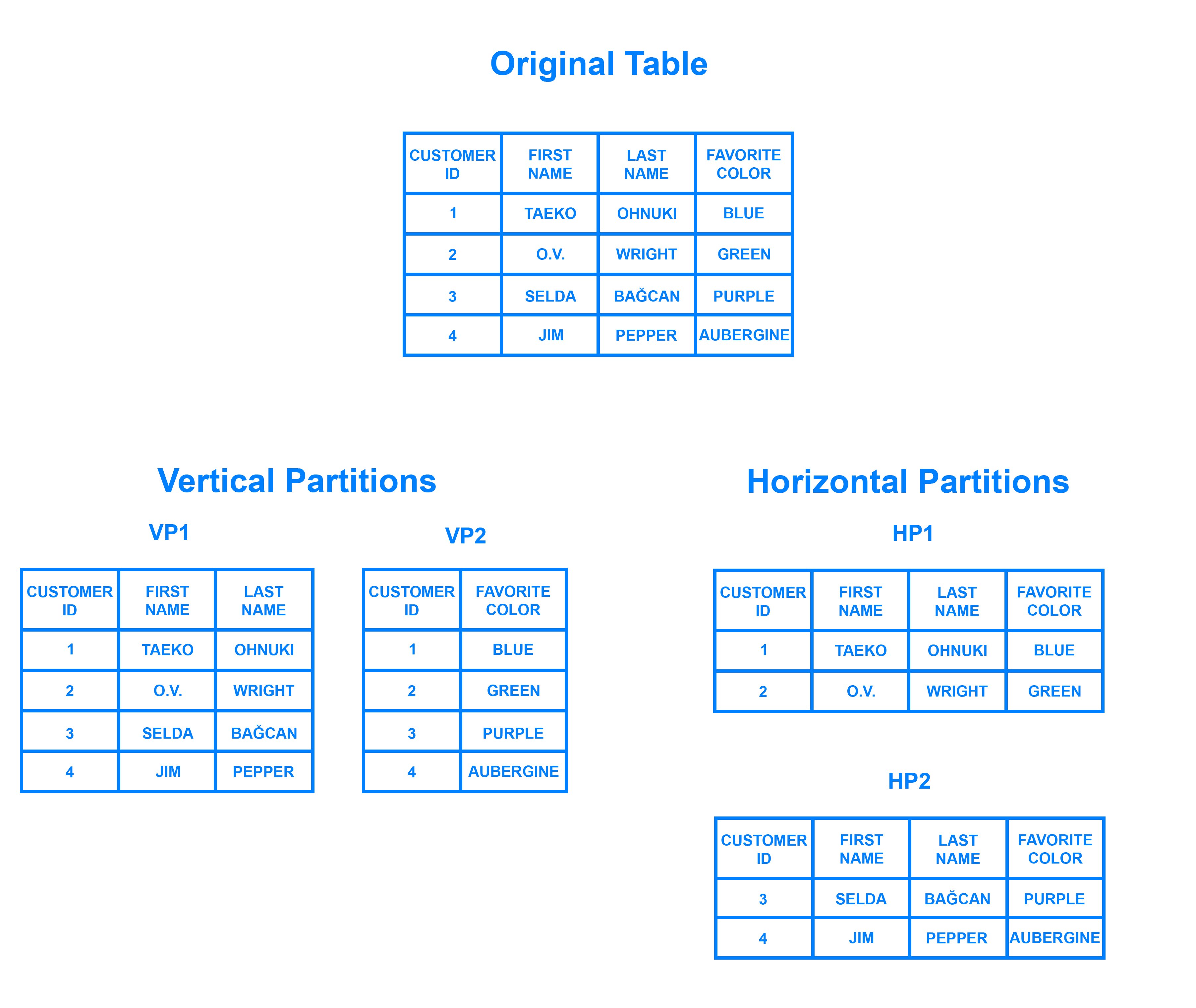

Sharding is a database architecture pattern related to horizontal partitioning — the practice of separating one table’s rows into multiple different tables, known as partitions. Each partition has the same schema and columns, but also entirely different rows. Likewise, the data held in each is unique and independent of the data held in other partitions.

It can be helpful to think of horizontal partitioning in terms of how it relates to vertical partitioning. In a vertically-partitioned table, entire columns are separated out and put into new, distinct tables. The data held within one vertical partition is independent from the data in all the others, and each holds both distinct rows and columns. The following diagram illustrates how a table could be partitioned both horizontally and vertically:

Sharding involves breaking up one’s data into two or more smaller chunks, called logical shards. The logical shards are then distributed across separate database nodes, referred to as physical shards, which can hold multiple logical shards. Despite this, the data held within all the shards collectively represent an entire logical dataset.

Database shards exemplify a shared-nothing architecture. This means that the shards are autonomous; they don’t share any of the same data or computing resources. In some cases, though, it may make sense to replicate certain tables into each shard to serve as reference tables. For example, let’s say there’s a database for an application that depends on fixed conversion rates for weight measurements. By replicating a table containing the necessary conversion rate data into each shard, it would help to ensure that all of the data required for queries is held in every shard.

Oftentimes, sharding is implemented at the application level, meaning that the application includes code that defines which shard to transmit reads and writes to. However, some database management systems have sharding capabilities built in, allowing you to implement sharding directly at the database level.

Given this general overview of sharding, let’s go over some of the positives and negatives associated with this database architecture.

Benefits of Sharding

The main appeal of sharding a database is that it can help to facilitate horizontal scaling, also known as scaling out. Horizontal scaling is the practice of adding more machines to an existing stack in order to spread out the load and allow for more traffic and faster processing. This is often contrasted with vertical scaling, otherwise known as scaling up, which involves upgrading the hardware of an existing server, usually by adding more RAM or CPU.

It’s relatively simple to have a relational database running on a single machine and scale it up as necessary by upgrading its computing resources. Ultimately, though, any non-distributed database will be limited in terms of storage and compute power, so having the freedom to scale horizontally makes your setup far more flexible.

Another reason why some might choose a sharded database architecture is to speed up query response times. When you submit a query on a database that hasn’t been sharded, it may have to search every row in the table you’re querying before it can find the result set you’re looking for. For an application with a large, monolithic database, queries can become prohibitively slow. By sharding one table into multiple, though, queries have to go over fewer rows and their result sets are returned much more quickly.

Sharding can also help to make an application more reliable by mitigating the impact of outages. If your application or website relies on an unsharded database, an outage has the potential to make the entire application unavailable. With a sharded database, though, an outage is likely to affect only a single shard. Even though this might make some parts of the application or website unavailable to some users, the overall impact would still be less than if the entire database crashed.

Drawbacks of Sharding

While sharding a database can make scaling easier and improve performance, it can also impose certain limitations. Here, we’ll discuss some of these and why they might be reasons to avoid sharding altogether.

The first difficulty that people encounter with sharding is the sheer complexity of properly implementing a sharded database architecture. If done incorrectly, there’s a significant risk that the sharding process can lead to lost data or corrupted tables. Even when done correctly, though, sharding is likely to have a major impact on your team’s workflows. Rather than accessing and managing one’s data from a single entry point, users must manage data across multiple shard locations, which could potentially be disruptive to some teams.

One problem that users sometimes encounter after having sharded a database is that the shards eventually become unbalanced. By way of example, let’s say you have a database with two separate shards, one for customers whose last names begin with letters A through M and another for those whose names begin with the letters N through Z. However, your application serves an inordinate amount of people whose last names start with the letter G. Accordingly, the A-M shard gradually accrues more data than the N-Z one, causing the application to slow down and stall out for a significant portion of your users. The A-M shard has become what is known as a database hotspot. In this case, any benefits of sharding the database are canceled out by the slowdowns and crashes. The database would likely need to be repaired and resharded to allow for a more even data distribution.

Another major drawback is that once a database has been sharded, it can be very difficult to return it to its unsharded architecture. Any backups of the database made before it was sharded won’t include data written since the partitioning. Consequently, rebuilding the original unsharded architecture would require merging the new partitioned data with the old backups or, alternatively, transforming the partitioned DB back into a single DB, both of which would be costly and time consuming endeavors.

A final disadvantage to consider is that sharding isn’t natively supported by every database engine. For instance, PostgreSQL does not include automatic sharding as a feature, although it is possible to manually shard a PostgreSQL database. There are a number of Postgres forks that do include automatic sharding, but these often trail behind the latest PostgreSQL release and lack certain other features. Some specialized database technologies — like MySQL Cluster or certain database-as-a-service products like MongoDB Atlas — do include auto-sharding as a feature, but vanilla versions of these database management systems do not. Because of this, sharding often requires a “roll your own” approach. This means that documentation for sharding or tips for troubleshooting problems are often difficult to find.

These are, of course, only some general issues to consider before sharding. There may be many more potential drawbacks to sharding a database depending on its use case.

Now that we’ve covered a few of sharding’s drawbacks and benefits, we will go over a few different architectures for sharded databases.

Sharding Architectures

Once you’ve decided to shard your database, the next thing you need to figure out is how you’ll go about doing so. When running queries or distributing incoming data to sharded tables or databases, it’s crucial that it goes to the correct shard. Otherwise, it could result in lost data or painfully slow queries. In this section, we’ll go over a few common sharding architectures, each of which uses a slightly different process to distribute data across shards.

Key Based Sharding

Key based sharding, also known as hash based sharding, involves using a value taken from newly written data — such as a customer’s ID number, a client application’s IP address, a ZIP code, etc. — and plugging it into a hash function to determine which shard the data should go to. A hash function is a function that takes as input a piece of data (for example, a customer email) and outputs a discrete value, known as a hash value. In the case of sharding, the hash value is a shard ID used to determine which shard the incoming data will be stored on. Altogether, the process looks like this:

To ensure that entries are placed in the correct shards and in a consistent manner, the values entered into the hash function should all come from the same column. This column is known as a shard key. In simple terms, shard keys are similar to primary keys in that both are columns which are used to establish a unique identifier for individual rows. Broadly speaking, a shard key should be static, meaning it shouldn’t contain values that might change over time. Otherwise, it would increase the amount of work that goes into update operations, and could slow down performance.

While key based sharding is a fairly common sharding architecture, it can make things tricky when trying to dynamically add or remove additional servers to a database. As you add servers, each one will need a corresponding hash value and many of your existing entries, if not all of them, will need to be remapped to their new, correct hash value and then migrated to the appropriate server. As you begin rebalancing the data, neither the new nor the old hashing functions will be valid. Consequently, your server won’t be able to write any new data during the migration and your application could be subject to downtime.

The main appeal of this strategy is that it can be used to evenly distribute data so as to prevent hotspots. Also, because it distributes data algorithmically, there’s no need to maintain a map of where all the data is located, as is necessary with other strategies like range or directory based sharding.

Range Based Sharding

Range based sharding involves sharding data based on ranges of a given value. To illustrate, let’s say you have a database that stores information about all the products within a retailer’s catalog. You could create a few different shards and divvy up each products’ information based on which price range they fall into, like this:

The main benefit of range based sharding is that it’s relatively simple to implement. Every shard holds a different set of data but they all have an identical schema as one another, as well as the original database. The application code reads which range the data falls into and writes it to the corresponding shard.

On the other hand, range based sharding doesn’t protect data from being unevenly distributed, leading to the aforementioned database hotspots. Looking at the example diagram, even if each shard holds an equal amount of data the odds are that specific products will receive more attention than others. Their respective shards will, in turn, receive a disproportionate number of reads.

Directory Based Sharding

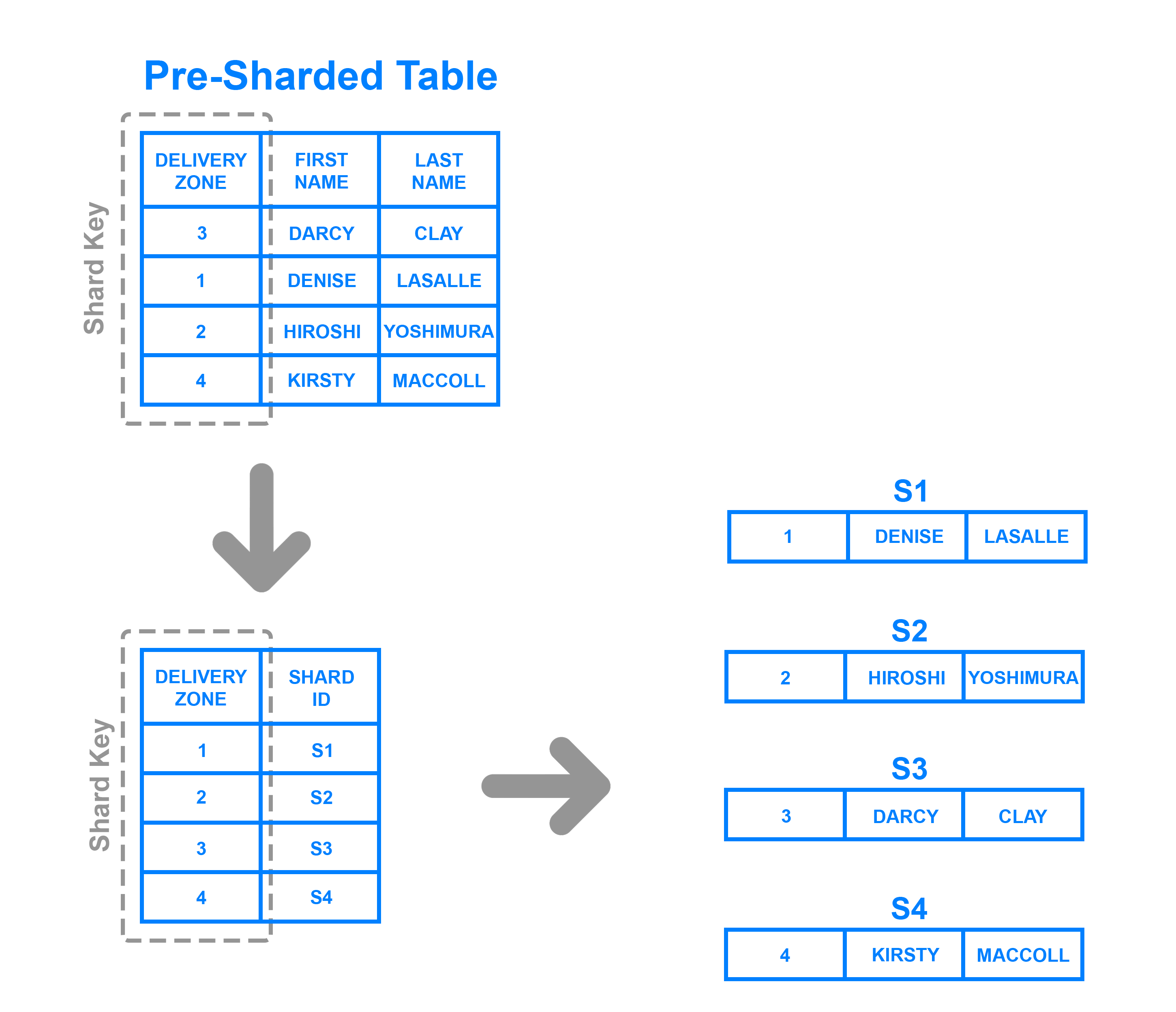

To implement directory based sharding, one must create and maintain a lookup table that uses a shard key to keep track of which shard holds which data. A lookup table is a table that holds a static set of information about where specific data can be found. The following diagram shows a simplistic example of directory based sharding:

Here, the Delivery Zone column is defined as a shard key. Data from the shard key is written to the lookup table along with whatever shard each respective row should be written to. This is similar to range based sharding, but instead of determining which range the shard key’s data falls into, each key is tied to its own specific shard. Directory based sharding is a good choice over range based sharding in cases where the shard key has a low cardinality — meaning, it has a low number of possible values — and it doesn’t make sense for a shard to store a range of keys. Note that it’s also distinct from key based sharding in that it doesn’t process the shard key through a hash function; it just checks the key against a lookup table to see where the data needs to be written.

The main appeal of directory based sharding is its flexibility. Range based sharding architectures limit you to specifying ranges of values, while key based ones limit you to using a fixed hash function which, as mentioned previously, can be exceedingly difficult to change later on. Directory based sharding, on the other hand, allows you to use whatever system or algorithm you want to assign data entries to shards, and it’s relatively easy to dynamically add shards using this approach.

While directory based sharding is the most flexible of the sharding methods discussed here, the need to connect to the lookup table before every query or write can have a detrimental impact on an application’s performance. Furthermore, the lookup table can become a single point of failure: if it becomes corrupted or otherwise fails, it can impact one’s ability to write new data or access their existing data.

Should I Shard?

Whether or not one should implement a sharded database architecture is almost always a matter of debate. Some see sharding as an inevitable outcome for databases that reach a certain size, while others see it as a headache that should be avoided unless it’s absolutely necessary, due to the operational complexity that sharding adds.

Because of this added complexity, sharding is usually only performed when dealing with very large amounts of data. Here are some common scenarios where it may be beneficial to shard a database:

- The amount of application data grows to exceed the storage capacity of a single database node.

- The volume of writes or reads to the database surpasses what a single node or its read replicas can handle, resulting in slowed response times or timeouts.

- The network bandwidth required by the application outpaces the bandwidth available to a single database node and any read replicas, resulting in slowed response times or timeouts.

Before sharding, you should exhaust all other options for optimizing your database. Some optimizations you might want to consider include:

- Setting up a remote database. If you’re working with a monolithic application in which all of its components reside on the same server, you can improve your database’s performance by moving it over to its own machine. This doesn’t add as much complexity as sharding since the database’s tables remain intact. However, it still allows you to vertically scale your database apart from the rest of your infrastructure.

- Implementing caching. If your application’s read performance is what’s causing you trouble, caching is one strategy that can help to improve it. Caching involves temporarily storing data that has already been requested in memory, allowing you to access it much more quickly later on.

- Creating one or more read replicas. Another strategy that can help to improve read performance, this involves copying the data from one database server (the primary server) over to one or more secondary servers. Following this, every new write goes to the primary before being copied over to the secondaries, while reads are made exclusively to the secondary servers. Distributing reads and writes like this keeps any one machine from taking on too much of the load, helping to prevent slowdowns and crashes. Note that creating read replicas involves more computing resources and thus costs more money, which could be a significant constraint for some.

- Upgrading to a larger server. In most cases, scaling up one’s database server to a machine with more resources requires less effort than sharding. As with creating read replicas, an upgraded server with more resources will likely cost more money. Accordingly, you should only go through with resizing if it truly ends up being your best option.

Bear in mind that if your application or website grows past a certain point, none of these strategies will be enough to improve performance on their own. In such cases, sharding may indeed be the best option for you.

Conclusion

Sharding can be a great solution for those looking to scale their database horizontally. However, it also adds a great deal of complexity and creates more potential failure points for your application. Sharding may be necessary for some, but the time and resources needed to create and maintain a sharded architecture could outweigh the benefits for others.

By reading this conceptual article, you should have a clearer understanding of the pros and cons of sharding. Moving forward, you can use this insight to make a more informed decision about whether or not a sharded database architecture is right for your application.

Thanks for learning with the DigitalOcean Community. Check out our offerings for compute, storage, networking, and managed databases.

This textbox defaults to using Markdown to format your answer.

You can type !ref in this text area to quickly search our full set of tutorials, documentation & marketplace offerings and insert the link!

Great article, thank you!

When it comes to building multi tenant applications there are generally 3 db options:

If I were to go with a shared db and an isolated schema, would I be able to shard based on the schema alone?

If so is this something I can do with DO’s managed database service, is sharding even a feature of DO’s managed dbs (given that postgres technically does not support it)?

good

Hi.

I want to implement Range Based Sharding based on a multistore app. So, each horizontal partition correspond to one merchant.

What tutorial do you recommend to implement it on MySQL?

Best regards

This comment has been deleted

good

Wonderful article.

Good knowledge…Thank You

Nice article. Thanks for sharing it.

Useful article - thanks!

Does the sharding (horizontal partitioning) still work if the original database is columnar?